Breaking Down The Carbon Tax Across What is Currently Canada

Authors

Nicola Radatus-Smith

My name is Nicola Radatus-Smith, I use the pronouns she/her and I am a second-generation Canadian of European descent and am residing in what is currently Toronto, Ontario. I acknowledge that this land was traditionally stewarded by many nations, including the Mississaugas of the Credit, the Anishnabeg, the Chippewa, the Haudenosaunee and the Wendat peoples and is now home to many diverse First Nations, Inuit and Métis peoples. As a settler, white, cis-gendered woman, I do not intend to speak for BIPOC communities but rather strive for allyship and use my privilege to bring attention to issues that have disproportionately impacted these communities. I acknowledge my privilege as being an educated woman, having a degree in biology and sustainability management which has broadened my understanding of environmental, social, economic, and government systems. I recognize these experiences shape my understanding of the world and am open to further education to better understand the experiences of others to tackle environmental justice challenges.

Jane Pangilinan

My name is Jane Pangilinan and I use she and her pronouns. I currently reside in what is currently known as North York, Ontario, Canada which is the land of the Huron-Wendat, the Seneca, Haudenosaunee, and the Mississaugas of the Credit River. I am relearning the meaning of living on lands of the Toronto Purchase Treaty 13, which holds a deep history of past and continuing hurt. This history is constantly shifted through one lens when so many other perspectives exist and become erased.

As a Filipino Canadian, I continue to learn what it means to be both immigrant and settler with the opportunities given to me. I thank my parents who come from Bulacan, Philippines and acknowledge that my lived experiences are unique and are not a full representation of this or any group. I am constantly inspired by my communities, ancestors, and heroes who paved the way for my aspirations to become reality. I hope to use my abilities as a Canadian citizen and researcher to uplift others.

Angelique

Editor

Megan Bureau, Anna Huschka & Hayley Brackenridge

What is the Carbon Tax?

Pollution is an unwelcome effect of the systems of our daily lives, and is difficult to rid of entirely. As a result, and in an effort to combat the effects of climate change, governments are looking into different ways to lower and mitigate pollution and the emission of greenhouse gases, including through the implementation of carbon pricing systems.

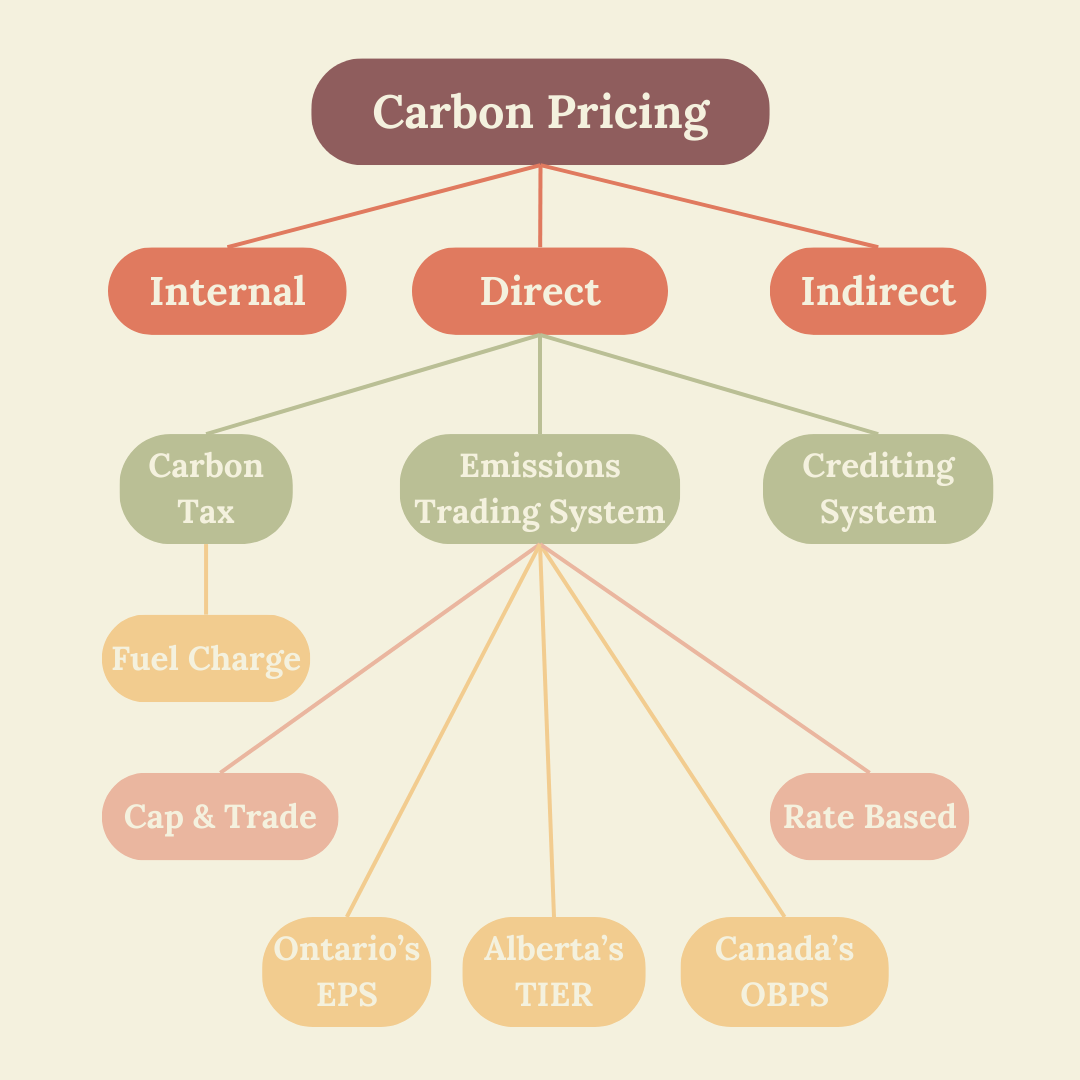

Carbon taxes are just one instrument under the umbrella of carbon pricing, which is the concept of connecting the social cost (e.g., impacts of resulting pollution on communities, people, and nature) to a monetary price on an amount of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions produced in an effort to lower emissions (1). Carbon pricing covers an umbrella of financial mechanisms or systems that function to regulate, deter, or reduce emissions, including carbon taxes, emissions trading system (ETS) like cap and trade, and crediting systems (1).

Specifically, carbon taxes are a defined rate on greenhouse gas emissions (GHG) set by governments. Carbon taxes charge a company a preset rate by the amount of carbon they emit, usually measured in tonnes, as those emissions are reported to the government (2).

The strategy behind carbon tax systems is to financially incentivize the reduction of emissions (1) while putting pressure or responsibility on those who create it. This is meant to put the financial burden on the producer and deter them from increasing emissions. Carbon tax is designed to work with markets as a price signal, meaning that the price put on carbon affects how it is consumed/supplied (2). Unlike traditional taxes, carbon taxes are an indirect tax because they are charged by transaction, whereas direct taxes are charged by income (3). For carbon taxes, the price is predetermined and the outcome is not guaranteed.

Carbon taxes are just one instrument under the umbrella of carbon pricing, which is the concept of connecting the social cost (e.g., impacts of resulting pollution on communities, people, and nature) to a monetary price on an amount of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions produced in an effort to lower emissions (1). Carbon pricing covers an umbrella of financial mechanisms or systems that function to regulate, deter, or reduce emissions, including carbon taxes, emissions trading system (ETS) like cap and trade, and crediting systems (1).

Types of Carbon Pricing Systems

Carbon pricing can be internal, indirect or direct (1).

Internal carbon pricing are practices inside companies that mitigate carbon emissions through pricing the carbon consumed, in an effort to reach carbon or climate neutrality (1).

Indirect carbon pricing affects the price of carbon or emissions without directly putting a price on the carbon itself (1). An example of this is a fossil fuel subsidy, a financial supplement usually from the government to consumers or producers of fossil fuels (4). The additional monetary support creates a price signal or change in fossil fuel prices even if it was utilized for a different purpose. To learn more about fossil fuel subsidies, see this article.

Direct carbon pricing is directly paying for emissions or the activities that produce them with specific intent on putting a price on the carbon emission or other types of fuel emissions (1). Emissions trading systems (ETS), carbon taxes, and carbon crediting systems are all examples of direct carbon pricing. An ETS will put a limit on emissions, allow for companies to have a set number of emission units to reach or stay under that limit, and allow companies to trade units between themselves in order to create a market for the sale of units (1).

Direct carbon pricing systems have been previously implemented by provincial governments across what is currently Canada. For example, in 2007 so-called Quebec implemented a direct carbon tax on larger polluters and distributors, such as industry, power, transport and buildings sectors (5). In 2008, what is currently British Columbia was the first to introduce a carbon tax that applied to all consumers of carbon fuels, where the money collected remained revenue-neutral, meaning the tax burden on citizens remains neutral as the carbon tax is raised by helping fund the reduction of other taxes in the province (6).

The famous cap and trade system is a type of emissions trading system. Cap-and-trade systems are used in the provinces of so-called Quebec, Ontario, and Alberta. In 2013, what is currently Quebec implemented cap-and-trade to replace their initial carbon taxing system, which allowed them to align with U.S. states like California when they adopted it in 2015 (5). So-called Ontario started their cap-and-trade pricing system in 2018, though it was quickly repealed by the following elected provincial government. The provincial government of so-called Ontario reinstated a cap-and-trade system based on intensity of emissions for large industrial emitters in 2022, called the Emissions Performance Standards (EPS) program (7). So-called Alberta has had a similarly complicated history of carbon pricing systems dating back to 2007. Since 2020 the provincial government of so-called Alberta has been operating the Technology Innovation and Emission Reduction (TIER) program, which focuses on industry polluters and drives emissions reduction through an emission trading system (8).

Carbon taxes are just one instrument under the umbrella of carbon pricing, which is the concept of connecting the social cost (e.g., impacts of resulting pollution on communities, people, and nature) to a monetary price on an amount of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions produced in an effort to lower emissions (1). Carbon pricing covers an umbrella of financial mechanisms or systems that function to regulate, deter, or reduce emissions, including carbon taxes, emissions trading system (ETS) like cap and trade, and crediting systems (1).

How does it work in a Canadian context?

At the federal level, the Greenhouse Gas Pollution Pricing Act (GGPPA) received royal assent in June 2018 (9). The Act recognizes the impacts of climate change across so-called Canada and the effectiveness of a carbon pricing system as a critical policy tool, following the polluter pays principle, to incentivize behavioural changes necessary for the reduction of global warming aligned with international agreements (10). This Act mandated a federal carbon pricing system, often referred to as the “federal backstop,” in provinces and territories that did not have their own sufficiently stringent carbon pricing systems (10, 11).

As per the Greenhouse Gas Pollution Pricing Act, there are two pricing systems:

The first part consists of a fuel charge, which is a national set price that increases over time. The fuel charge covers pricing for different types of fuel and combustible waste in relation to carbon dioxide emissions (CO2e) (12) and is paid by fuel distributors and other registered people with business activities related to fossil fuels like emitters or users as seen in this list (13). As of 2023, the current fuel charge is $65 per tonne (12). The fuel charge will increase on a pricing trajectory, developed by the federal government through factors determined by Environment and Climate Change Canada, with a goal of reaching $170 per tonne by 2030 (12).

The fuel charge covers different fuel types including coal, diesel, gasoline, kerosene, jet fuel, liquefied petroleum gas (LPG), natural gas, and other oil products (14). To account for different fuel dependencies by each territory or province, the government adjusted the fuel charge to differ in some areas as needed, for example, Nunavut and Yukon are exempt from aviation-related charges (12).

The second part of the federal carbon pollution pricing system is the Output-Based Pricing System (OBPS). This is an emissions trading system (ETS) that uses a price ceiling, setting a baseline, allowing for trade of credits, and setting a minimum national carbon price which started at $65 in 2023 and is set to raise by $15 per year (15). Paying for carbon emissions is required by law for those in key emissions-intensive and trade-exposed (EITE) industries like electrical and industrial sectors (16). The baseline is a set minimum of emissions that companies are expected to stay under. When companies maintain emissions under the baseline, they are able to attain credits for their “leftover space” under the minimum. They can then sell those credits to companies who are looking to go over the baseline. Going over the yearly limit of emissions can result in paying an amount for the difference. Companies may choose to relocate to different areas in an effort to avoid carbon pricing, this is known as “carbon leakage”.

Provincial and territorial governments have the choice between using the federal system or designing their own to meet their specific needs and circumstances, but the system must follow the specific standards set by the federal government (17). These standards are also known as the federal benchmark (11). The money collected from the carbon pricing system goes towards clean technology developments, returns to the public in the form of the Canada Carbon Rebate, and other initiatives set by the government (14, 17).

To learn more about province- or territory-specific systems, check out the links below:

- Alberta TIER

- British Columbia Offset Program

- British Columbia OBPS

- Manitoba

- New Brunswick OBPS

- Newfoundland and Labrador PSS

- Northwest Territories

- Nova Scotia OBPS and Crediting Mechanism

- Ontario EPS

- Quebec CaT

- Quebec Offset Crediting Mechanism

- Saskatchewan OBPS

You can also learn more about carbon pricing and the OBPS using the World Bank’s Carbon Pricing Dashboard.

Challenges to implementing the GGPPA

Following the passage of the GGPPA, the provincial governments of so-called Saskatchewan, Ontario, and Alberta, appealed to the Supreme Court of Canada arguing it was unconstitutional, as the Constitution Act, 1867 defines that it is the responsibility of provinces to handle decisions related to environmental protection and pollution (18, 19). On March 25, 2021, the Supreme Court of Canada upheld the constitutionality of the GGPPA in a split decision of 6-3 (20), which you can read more about here. The court ruled that the federal government has the authority to enact the GGPPA under the national concern branch of the peace, order, and good government (POGG) clause of the Constitution Act, 1867 (20). This clause allows the federal government to legislate on matters of national concern that are beyond provincial jurisdiction.

There were a few key implications that emerged from the Court’s decision. First, climate change was identified as an issue of national concern, needing a coordinated response to deal with the cumulative dimensions of GHG emissions beyond individual provincial action (20). Secondly, the ruling indicates that the federal government has the jurisdictional duty to address matters that have national and international implications, in this case being climate change, setting a precedent for future decision making (20).

Additionally, the Court’s decision has key implications for the judicial handling of climate matters in the future. It demonstrates a recognition of climate change as a national threat and provides precedents for future legal rulings where environmental, social, and legal implications of climate change are confronted (18).

Helpful Definitions

Cap and Trade System: A type of emissions trading system (ETS) that uses a limit or cap and financial incentive to reduce emissions (21)

Carbon Leakage: When a company makes the decision to move to a place with a less strict policy regarding carbon pricing often resulting in more emissions (22)

Carbon Pricing: According to the World Bank, carbon pricing is “an instrument that captures the external costs of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions” (2)

Carbon Tax: A set price on a tonne of carbon emissions, can also refer to the system that creates a definite rate on carbon/greenhouse gas emissions (1)

Emissions Trading System (ETS): The system that creates a carbon trading market through the use of a limit on emissions and the ability to trade “allowances” or emissions units (1)

Federal Benchmark: Benchmark criteria set out by the federal government to determine carbon pricing systems across Canada (17)

Federal Backstop: The federal system of carbon pricing put in place where a province or territory does not have a different system/approach to meeting the carbon pricing system criteria (17)

Fuel Charge: Canada’s national carbon tax on 21 different fuel types (14)

Output-Based Pricing System (OBPS): Canada’s national emissions trading system (ETS) in provinces or territories that opted into it or do not already have a system in place (14)

Price Signal: (In the context of carbon pricing) When setting a price affects the supply and demand of carbon or other fuel types that release greenhouse gas emissions (23)

Price Floor: A set limit of how low a price can be, often set by governments (24)

Pricing Trajectory: The trajectory to which the carbon tax (or fuel charge in Canadian context) raises annually

Learn More

Carbon pricing:

- Carbon Pricing Dashboard by World Bank

- Systems Change Lab’s analysis of carbon pricing

- Canadian Climate Institute’s Climate Policies analysis

- Detailed information on OBPS from World Bank

Carbon tax across the provinces can be found here:

Policy Brief: Shake Up The Establishment’s Feedback on the National Framework for Environmental Learning

References

- World Bank. State and trends of carbon pricing dashboard [Internet]. World Bank; [cited 2024 Jul 29]. Available from: https://carbonpricingdashboard.worldbank.org/about

- World Bank. What is carbon pricing? [Internet]. World Bank; 2024 [2024 Jul 29]. Available from: https://carbonpricingdashboard.worldbank.org/what-carbon-pricing

- Wikipedia. Carbon tax [Internet]. Wikipedia; [modified 2024 Sep 3, cited 2024 Jul 29]. Available from: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Carbon_tax#:~:text=A%20carbon%20tax%20is%20an,rather%20than%20an%20emission%20limit

- International Institute for Sustainable Development. Unpacking Canada’s fossil fuel subsidies [Internet]. International Institute for Sustainable Development; 2020 Dec 11 [cited 2024 Sep 13]. Available from: https://www.iisd.org/articles/unpacking-canadas-fossil-fuel-subsidies-faq

- World Bank. Quebec CaT [Internet]. World Bank; [edited 2023 Apr 1, cited 2024 Sep 13]. Available from: https://carbonpricingdashboard.worldbank.org/compliance/factsheets?instrument=ETS_CA_Quebec

- Elgie, S., & McClay, J. (2013). BC’s carbon tax shift is working well after four years (Attention Ottawa). Canadian Public Policy, 39 (Supplement 2), S1–S10. https://doi.org/10.3138/CPP.39.Supplement2.S1

- World Bank. Ontario EPS [Internet]. World Bank; [edited 2023 Apr 1, cited 2024 Sep 13]. Available from: https://carbonpricingdashboard.worldbank.org/compliance/factsheets?instrument=ETS_CA_Ontario2

- Government of Alberta. Technology innovation and emissions reduction regulation [Internet]. Alberta: Government of Alberta; [cited 2024 Jul 5]. Available from: https://www.alberta.ca/technology-innovation-and-emissions-reduction-regulation

- Government of Canada. Greenhouse gas pollution pricing act [Internet]. Canada: Government of Canada; 2024 Jun 20 [cited 2024 Jul 5]. Available from: https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/g-11.55/page-1.html

- Government of Canada. Greenhouse gas pollution pricing act, S.C. 2018, c. 12 [Internet]. Canada: Government of Canada; [cited 2024 Sep 13]. Available from https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/G-11.55/

- Government of Canada. Carbon pollution pricing systems across Canada [Internet]. Canada: Government of Canada; [edited 2024 May 3, cited 2024 Sep 13]. Available from: https://www.canada.ca/en/environment-climate-change/services/climate-change/pricing-pollution-how-it-will-work.html

- Government of Canada. Fuel charge rates [Internet]. Canada: Government of Canada; 2024 [cited 2024 Aug 27]. Available from: https://www.canada.ca/en/revenue-agency/services/forms-publications/publications/fcrates/fuel-charge-rates.html

- Government of Canada. Fuel charge registration [Internet]. Canada: Government of Canada; [edited 2023 Nov 28, cited 2024 Sep 13]. Available from: https://www.canada.ca/en/revenue-agency/services/tax/excise-taxes-duties-levies/fuel-charge/registration.html

- World Bank. Canada federal fuel charge [Internet].World Bank; [edited 2023 Apr 1, cited 2024 Sep 13]. Available from: https://carbonpricingdashboard.worldbank.org/compliance/factsheets

- World Bank. Northwest territories carbon tax [Internet]. World Bank; [cited 2024 Sep 13]. Available from: https://carbonpricingdashboard.worldbank.org/compliance/factsheets?instrument=Tax_CA_NT

- World Bank. Canada federal OBPS [Internet]. World Bank; [cited 2024 Sep 13]. Available from: https://carbonpricingdashboard.worldbank.org/compliance/factsheets?instrument=Tax_CA_NT

- Government of Canada. The federal carbon pollution pricing benchmark [Internet]. Government of Canada; 2024 [cited 2024 Jul 29]. Available from: https://www.canada.ca/en/environment-climate-change/services/climate-change/pricing-pollution-how-it-will-work/carbon-pollution-pricing-federal-benchmark-information.html

- Gurza Lavalle, A., & Phillips, P. Towards a progressive trade agenda for environmental goods and services: Key issues and challenges [Internet]. 2021: UBC Law Review; [cited 2024 Sep 13]. Available from: https://commons.allard.ubc.ca/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1707&context=fac_pubs

- CBC News. Supreme Court rules federal carbon pricing law constitutional [Internet]. Canada: CBC News; 2021 Mar 25 [cited 2024 Sep 13]. Available from: https://www.cbc.ca/news/politics/carbon-tax-supreme-court-1.5968284

- Government of Canada. References re greenhouse gas pollution pricing act [Internet]. Canada: Government of Canada; 2021 [cited 2024 Sep 13]. Available from: https://decisions.scc-csc.ca/scc-csc/scc-csc/en/item/18781/index.do

- Center for Climate and Energy Solutions. Cap and trade basics [Internet]. [edited 2024 May, cited 2024 Sep 13]. Available from:

- CLEAR Center. What is carbon leakage? [Internet]. UC Davis; 2020 Apr 24 [cited 2024 Sep 13]. Available from: https://clear.ucdavis.edu/news/what-carbon-leakage

- Capital. What is a price signal? [Internet]. Capital; 2024 [cited 2024 Sep 13]. Available from: https://capital.com/price-signal-definition

- Mitchell, C. Floor: what it is and what it means for traders [Internet]. Investopedia; 2023 Dec 27 [cited 2024 Sep 13]. Available from: https://www.investopedia.com/terms/f/floor.asp